Guest post by Kate Gladstone, author of READ CURSIVE FAST

BACKGROUND

Most folks today don’t write in cursive. Some people never even pick up a pen or pencil. Yet reading cursive remains an important life skill, whenever:

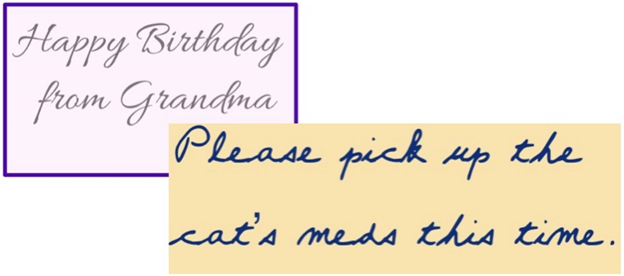

- family members use cursive, or send greeting cards that use cursive fonts:

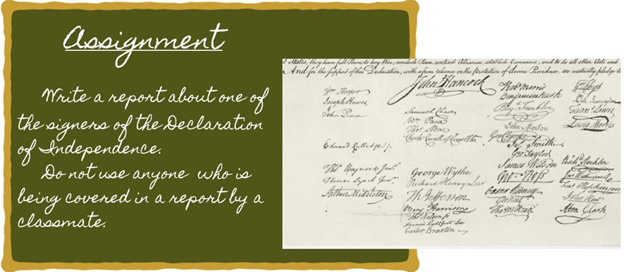

- teachers use cursive, or assign work that involves reading historical documents in the original form:

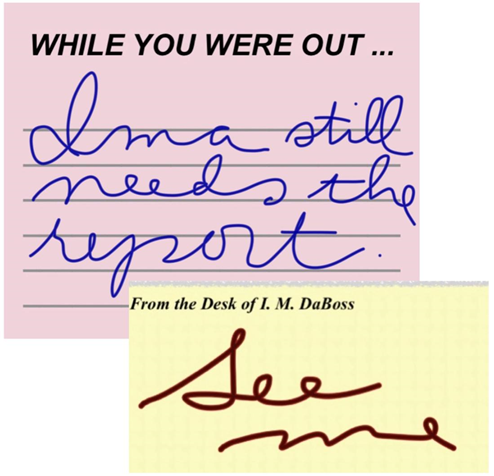

- employers, supervisors, or co-workers use cursive:

- store signs or logos use cursive:

Today, more and more children and adults — with and without disabilities — cannot read cursive handwriting, even when it is perfectly formed. In the USA, Canada, and India, for instance, non-readers of cursive include most people born after 1985 (in other words, most people 35 and under).

However, the “cursive non-reader” population also includes many adults above age 35. Most but not all of the older group are people with neurological disabilities or other differences affecting written language skills and/or visual perception. These cases occur at all educational and socioeconomic levels.

Strangely, today’s millions of “cursive non-readers” (with and without disabilities) aren’t limited to those who were never taught cursive writing. Cursive non-readers include many children, teens, and adults (at all educational levels) who actually had been required to learn cursive writing at some point. Sadly, tracing and copying page after page of cursive examples doesn’t guarantee that every student will somehow just “pick up” the ability to read whatever he or she is tracing and copying.

Worse yet: even when conventional cursive training actually does lead to reading (and writing) cursive, those “successful” learners often lose the ability sometime between the year that they are taught cursive (typically Grade 2 or 3) and the year that they leave high school.

This situation was profiled in 2013 by one of Canada’s largest newspapers.

The cursive non-readers interviewed in that article were college freshmen. By now, seven years later, they must be in their mid-twenties: they have jobs, or are trying to get jobs, and probably some of them have families. (How will cursive non-readers help their children, if the school or the district or other administration mandates cursive instruction?)

The causes of the problem (and the reasons it has peaked among those born since 1985) are numerous and important. However, space limitations require focusing this essay on what to do for cursive non-readers: how to make sure that everyone who reads print can read cursive, and how to make sure that the skill does not fade away as the student “ages out” of handwriting instruction.

How can we make cursive make sense to readers — even if they don’t write cursive? A new book, READ CURSIVE FAST (National Autism Resources, 2021), tackles the neglected issue.

Step One: Show how cursive letters happened!

When readers are allowed and encouraged to learn how cursive letters came about, remembering the cursive shapes makes cognitive sense, and does not have to rely solely on rote memory. Here’s an example for the letter G:

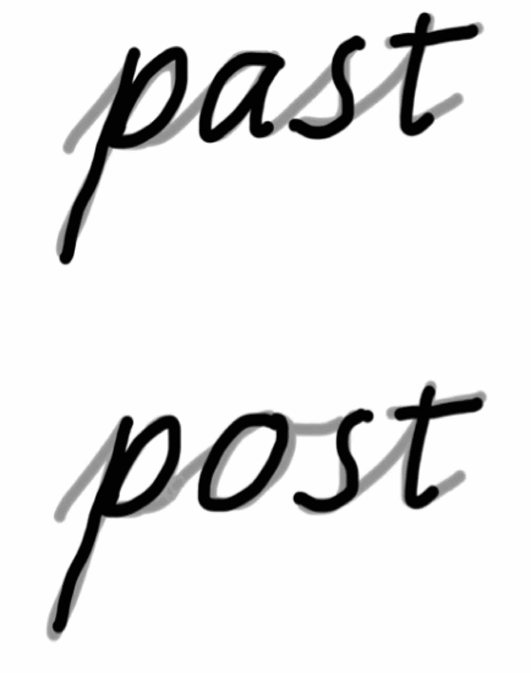

READ CURSIVE FAST uses a pattern-recognition/cognitive approach to “unlock” every cursive letter. Some letters need to be cracked in step-by-step detail, while others can be “cracked” more simply:

When you see the print-style s hiding inside cursive s, you can see why the cursive s looks different after lowercase o versus the way it looks after lowercase a.

Building pattern recognition and understanding into the learning task makes for faster progress and greater retention, by providing another route to comprehension. Cursive writing is not the only path to cursive reading — for many students, it is not even a reliable path.

Step Two: Sustained Reading

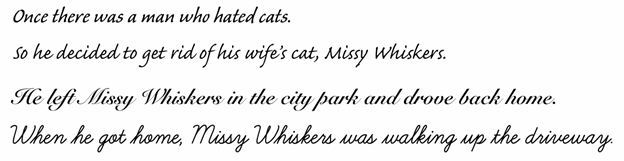

Once students recognize cursive letters alone and in words and phrases, it’s time to build automaticity and fluency with longer texts. To accomplish this, READ CURSIVE FAST uses “cursive stories”: passages written in fonts that resemble increasingly difficult styles of handwriting. Here is the opening of one story:

___________________________________________

[The first four sentences of a cursive story from READ CURSIVE FAST. ]

___________________________________________

The beginning of each story resembles familiar printed letters, but each sentence adds more and more cursive features, carefully easing readers into understanding increasingly complex forms of cursive.

Step Three: Reading Historical Documents

Once students can read present-day cursive with some fluency, they will eventually want or need to read our nation’s historical documents, many of which are written in very elaborate forms of cursive.

Today, reading historical documents is one of the most frequent reasons for needing to read cursive, but handwriting style variations in past centuries were even more frequent than they are today. This means that most students (particularly those with neurological issues) will benefit from practice with historical cursive samples once they are experienced in reading present-day cursive samples.

Therefore, READ CURSIVE FAST includes a section specifically on historical documents. Learners reach this point are usually pleased and amazed that they can now read historical material.

As the author of READ CURSIVE FAST, I look forward to seeing and hearing your own experiences and thoughts on cursive reading issues.

Buy now on Amazon or directly from the publisher!